AUTOS CHEAT SHEET

Source: Chevrolet

But chances are, you don’t. Because the Corvair myth is largely that: a myth. In reality, it was the right car at the wrong time: a groundbreaking model that could’ve set Detroit on a completely different path had it caught on, which it almost did. Besides, at the end of the day, it wasn’t Nader that did it in, it was something much closer to home. Half a century on, the Corvair is still the biggest gamble General Motors ever took on a single car, and for that alone, it deserves its due.

Source: General Motors

Detroit made cars for good drivers; bad drivers were the ones who got into crashes, and adding “safety features” to a car implied that you may be the one in a crash. Why would you need those? You aren’t a bad driver, are you?

So while Detroit’s general idea of safety hadn’t changed much since Ford decided to add rear brakes to the Model A (the Blue Oval even had the gall to try pushing seat belts on their ’55 models — customers hated them), the Big Three had become aware of a new phenomenon creeping into the market: imports.

They seemed to be seeping in from the top and bottom of the market: funny looking rear-engined offerings from companies called Renault and Volkswagen were wooing budget-minded buyers at the low end, and the country club set was beginning to pay attention to cars from Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar.

World War II was over, hundreds of thousands of Americans had been overseas, and jet travel had suddenly made the world feel a lot smaller.

By the mid ’50s, it said something to be “Continental,” and have a bit of old-world flair. Studebaker sold its Raymond Loewy-designed cars on their “

Source: Chevrolet

Cole had been interested in an air-cooled rear-engined, rear-wheel drive compact car since at least 1955, but the old guard at General Motors had long been resistant to a compact, and would likely blanch at something so revolutionary.

After taking the reins at Chevy, Cole continued to work on the project covertly, working with engineers from GM’s European Opel and Australian Holden divisions as cover. The recession changed some important minds at GM however, and by 1958, Cole’s running prototype (badged as a Holden) got the green light for production as a 1960 model.

Dubbed the Corvair (a name taken from a 1954 Corvette fastback show car), Chevy’s revolutionary compact was released to positive press on October 2, 1959. Starting at just over $2,000 (around $16K today), it was the cheapest Chevy available, and radically different from the competition’s new for ’60 subcompact offerings:

the Ford Falcon and Chrysler’s Valiant sub-brand. With an open, airy cabin, frontal trunk and fold-down rear seat (standard on coupes, optional on sedans), great handling for the era, great fuel economy (and estimated 20–25 miles per gallon), and an industry first air-cooled flat-six engine (beating Porsche by several years), the Corvair was a lot more car than Volkswagen and Renault could offer.

But buyer response wasn’t as expected; Americans were flocking to the more traditional, slightly cheaper Falcon over the radical Chevy. As a response, Cole ordered a crash program to field a more conventional compact (it would become the 1962 Chevy II Nova), and scrambled to reposition the Corvair in the Chevy lineup. Just three months into production, the Corvair was in trouble.

Source: Chevrolet

the Monza. Available at dealerships in May, the Monza featured bucket seats, a four speed manual transmission, a tuned engine putting out 95 horsepower, and a long options list allowing buyers to personalize their cars. By 1961, over 50% of Corvairs were sold with the $189 Monza package, and Chevrolet was selling over 330,000 of its rear-engined cars in ’61 and ’62.

In April 1962, the groundbreaking Corvair became the first production car to offer a turbocharged engine. While it was a $300 option, it cranked out 150 horsepower and 210 pound-feet of torque — an impressive figure for a relatively small engine. With its low center of gravity, great traction, and power, the turbocharged Corvair was beginning to get a reputation as something of a budget performance car. But it was also beginning to get a reputation for the wrong reasons too.

Source: Chevrolet

Driven around corners in anger, the rear end of the Corvair could cut loose, causing the outside rear wheel to “tuck under,” and break the car into a spin. This tendency, coupled with Detroit’s emphasis (or lack thereof) on safety made for a deadly combination.

The Corvair was supposed to come equipped with an anti-roll bar, but last-minute cost-cutting measures meant it was deleted just before production. As a stop-gap, Chevy advised dealers and buyers to fill the front tires to 15 psi, and the back with 26.

This worked fine, until the unsuspecting good driver pulled into a gas station and told the attendant to fill ’em up. By 1964, Chevy had addressed the problem by adding the front anti-roll bar and revising rear suspension, but by then, the damage had already been done.

Source: Mecum Auctions

And it is here too, that we have to go on record and say that the Corvair is – in our opinion – the most important new car of the entire crop of ’65 models, and the most beautiful car to appear in this country since before World War II.

With the Chevy II fighting the Falcon, and the Corvair no match for the Mustang, Chevy began developing its own ponycar. The Camaro would be ready by late 1966, and the Corvair would be largely irrelevant in the Chevy lineup.

Source: Mecum Auctions

In the book, the chapter is called “The Sporty Corvair-The One-Car Accident,” and was based on an interview with George Caramagna, a Chevy engineer who warned of the dangers of removing the anti-roll bar back in ’59. As the rest of the book goes on to describe the dangers of everything from interior brightwork, confusing gear selectors, Detroit’s indifference to safety (who knew there were so many bad drivers out there?), and what happens to the human body in a car crash, it painted a grotesque and ghoulish picture of the state of the automotive industry.

As Unsafe at Any Speed became the unlikely best-seller of 1966, Chevy tried to bury the Corvair in its lineup. Plenty of other cars had the same problems as the early Corvairs, and a number of other cars are excoriated in the book, but with it in such a prominent place in Nader’s book, the car became a symbol of everything that was wrong with the industry.

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson created the Department of Transportation to enforce safety standards on American roads, mandating features like collapsable steering columns, seat belts, and side-marker lights be standardized on all cars sold in the U.S. after 1968. The industry was changing fast, and the Corvair was sales poison. Sales fell to 30,000 in 1967, then 15,000 in ’68. In 1969, the Corvair was unceremoniously axed in May, after finding just 6,000 buyers.

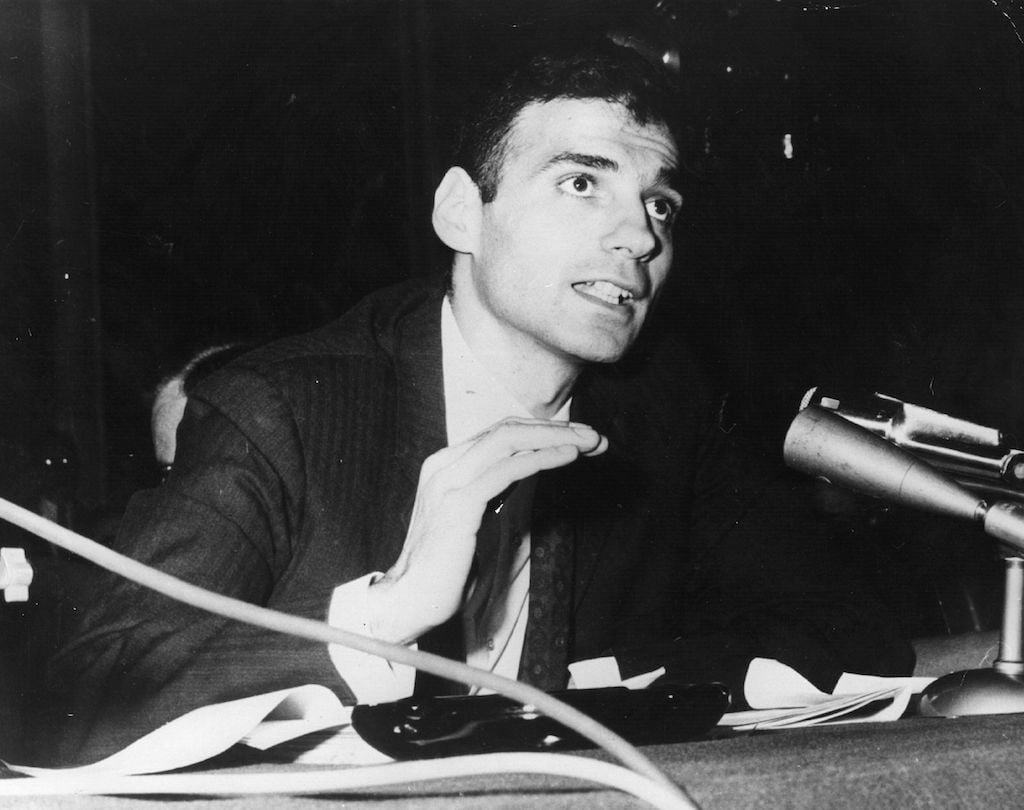

Ralph Nader | Keystone/Getty Images

The irony here is that by the early ’70s, the ponycar boom that damaged the Corvair was largely over thanks to safety and emissions standards, with millions or Americans flocking to affordable imports — the very cars the Corvair was designed to compete with. By the end of the decade, Detroit was losing ground as Japanese brands invaded the market, and by end of the 1980s, GM’s market share was a shadow of what it was when the Corvair debuted in ’59.

Source: Mecum Auctions

And with the price of early long-nose Porsche 911s going through the roof, sporty Monza and Corsa models offer spirited ’60s-era flat-six driving at a fraction of a price.

Imagine a world where the Corvair outsold the Falcon, and the Monza spurred Ford to build an air-cooled competitor. Would 20-plus miles per gallon have become the norm by the 1973 oil crisis? Would we have had a world of air-cooled flat-six performance cars to take on the Porsche 911?

Hell, would turbocharging have taken off a decade earlier? Today, the Corvair is an evolutionary dead end on the American automotive family tree, but it sure is a tantalizing what-if. Nader’s exposé on the automotive industry ultimately did more harm than good, and we can’t imagine the world without the Mustang, but we’d love to get a glimpse of a world where GM’s biggest gamble paid off.

Check out Autos Cheat Sheet on Facebook and Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment